李少君诗集《我是有大海的人》在英国出版

编者按

大自然是造物主,是万物赖以生存的神奇家园,也是人类文化和价值的重要体现。在大自然的指引之下,人们得以找回自己的本真,收获诗意。

出生于湖南湘乡的中国代表诗人李少君,始终“走不出”他心爱的故土。湖湘的自然风光、人文景致,无声无息地成为了刻在他骨子里、流淌于血液中的DNA,滋养着他的生命和精神世界,渗透进他的思想和诗歌。

40多年来,自然、人文、情感这三大主题始终贯穿着李少君的诗歌创作。在他看来,“诗学就是情学”。 人本质上是情感的存在,而“情”往往寄于山水之中,那些人们竭力追寻的诗意,往往就是他笔下最简单、最纯净、最自然的万物生长,以及对日常生活的细微观察。因而他也被冠以“自然诗人”的称号。

李少君毕业于武汉大学,曾任《天涯》杂志主编,现任中国作家协会《诗刊》社主编,一级作家。

“人诗互证”,是李少君坚持提倡的写作主张,他认为,“写诗,就是要呈现真正的自我,就是要展示活生生的灵魂和精神”,只有真实的生活感与现场感,才能提供真正的情绪价值,反映出真正的主体精神。这同时也是中国古典诗歌的其中一个创作原则,即“触景生情,有感而发”。中国古典诗歌强调抒情、咏怀、言志,李少君将其作为他创作的根基,立足于自我主体的诗歌表达。这就是为什么李少君那平白简练的语言能有击中人心的力量。

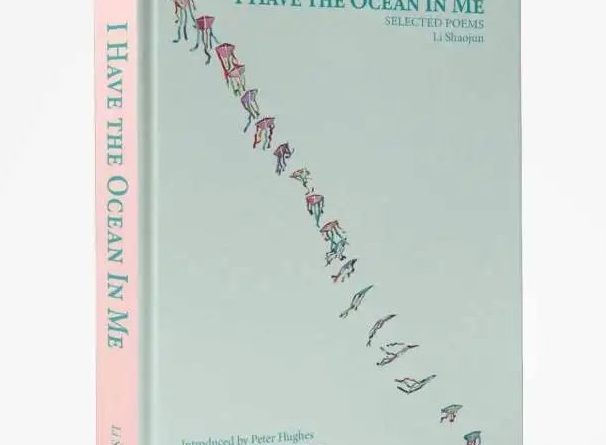

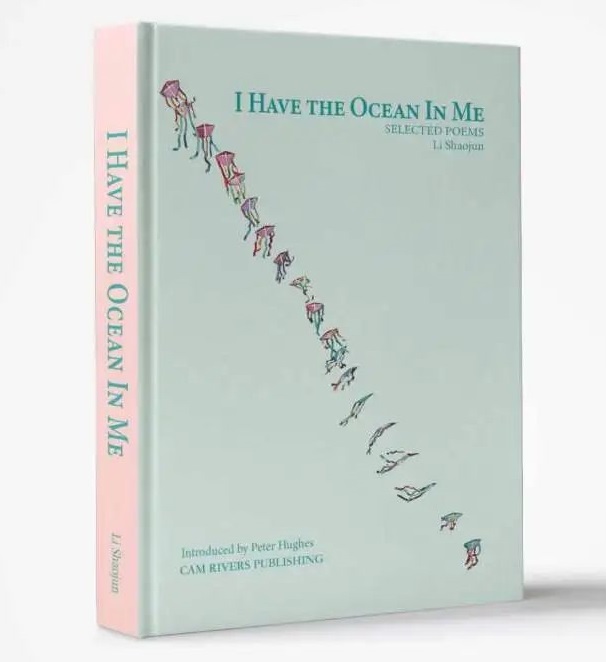

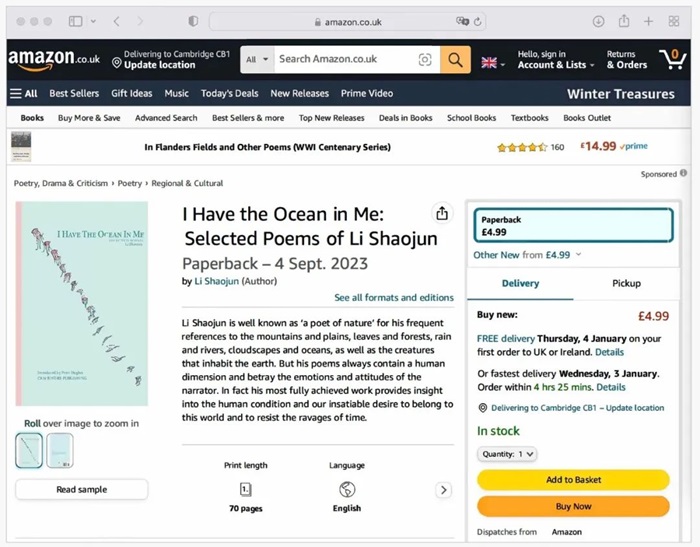

英国剑桥康河出版社从李少君的众多诗歌作品中,精选出了30首经典的诗歌,由名家翻译成英文、撰写序言,收录在了他名为 I Have the Ocean in Me:Selected Poems of Li Shaojun (《我是有大海的人:李少君诗歌精选集》)的诗集当中,并于2023年9月在英国剑桥举办的第九届“剑桥徐志摩诗歌艺术节”期间正式出版,全球发行。

新书首发

《我是有大海的人:李少君精选诗歌集》

【作者】李少君

【译者、 校审】王美富、苏浪禹、Peter Hughes

李少君诗集《我是有大海的人》英文版

I Have the Ocean in Me:

Selected Poems of Li Shaojun

在亚马逊12个国家站点有售

诗集介绍

本诗集选取李少君最具有代表性的其中一首诗歌《我是有大海的人》作为总标题,不仅展现了诗人对于自己人生的回顾,也代表了“自然成就生命、安置灵魂”这一贯穿全本的诗歌主题。诗人走过无数山川湖海,在旅途中将自己对自然观察中的所见所闻、所思所想凝结成诗句,彰显人性的光辉,拥抱那些脆弱而可贵的情感。

他曾久居海口,吸收大海给予他的精华与灵感,加深了他对海洋的理解和领悟。从某种程度上来看,海洋世界成为了他诗歌创作中一个非常重要的基础元素。

本书由著名英国诗人、剑桥大学朱迪斯·威尔逊基金诗歌项目客座专家、剑桥大学莫德林学院在诗歌领域的客座院士、剑桥康河出版社资深编辑彼得·休斯(Peter Hughes)担任主编,并撰写诗评。

彼得·休斯

本书封面插图,由著名艺术家、英国皇家水彩协会前主席大卫·帕斯凯特(David Paskett)亲手创作。帕斯卡特主席非常欣赏李少君诗歌作品中所蕴含的想象力,以及充满意境的画面感。他认为李少君的作品体现了文学与艺术的完美结合,不仅仅吸引了诗歌爱好者,也给来自不同文化背景的艺术家带来无限的启发。

大卫·帕斯凯特

这本诗集被收录在英国剑桥“康河CamRivers”国际诗人作品精选(中英文双语)百卷本之中。这套丛书是目前在中国海外出版的,规模最大的中英文双语个人诗歌作品精选集之一,是康河出版社在中外文学交流方面的重点项目。

目前已有四十余位来自世界各地的诗人与康河出版社签约,将他们的个人作品精选集出版、收录在这套系列丛书当中。

该系列丛书充满创意地跨界多个文学艺术门类,包括文学、音乐、绘画、朗诵艺术等。其中部分诗歌,由中英两地知名作曲家谱曲、两地音乐家演奏与演唱。图书的封面与插图,来自于各国艺术家。诗歌的有声版,由著名学者、社会活动家、诗人与艺术家等不同领域的专业人士演绎。

为李少君诗集作序

彼得·休斯

Peter Hughes

李少君被誉为“自然诗人”,他的诗中常常提及山川和平原、树叶和树林、雨水和河流、云景和海洋,以及栖息在地球上的各种生物。但他的诗歌总是包含人性化的一面,并背离叙事者的情感和态度。事实上,他最出彩的作品呈现了对人类境况的洞察,以及我们对于归属这个世界和抵抗时间摧残的无尽渴望。

当然,他的诗的确经常展现自然现象。例如,在《西湖,你好》这首诗的前四行诗节中,我们就看到了不下七种植物:

风送荷香,构成一个安逸的院落

紫薇,玉兰,香樟,银杏,梧桐

还有莺语藏在柳浪声中

正适合,散步一样的韵味和韵脚

这不仅仅是一份植物的名称列表。诗人引领我们去留意微风的轨迹,它夹带着那些植物的气味,以及鸟的歌声吹过。作者告诉我们,这一切构成了一个“诗意的空间”,如此缓慢的节奏,非常符合诗歌的意境。因此,文学的感召既关乎于“自然”,也与艺术息息相关。

同样,在本诗的第二节中,野禽和松鼠的出现也是带有情感色彩的。相反,诗人和鸟儿的相遇让双方都受到了惊吓,以至于野鸭害怕地逃走了。我们推断,正是这种干扰使松鼠从作者身边逃窜到了森林中。接着,第三节描写了正在草地上觅食的鸟儿,“我一过去,它们就四散而逃”。第四节,也就是诗歌的最后一节写道:

所以,近来我有着一个迫切的愿望

希望尽快认识这里所有的花草鸟兽

我们可以看到,这首诗让读者感受到了大自然的脆弱和不稳定。这些生物总是时刻准备着从我们身边逃离,也许,我们永远不会再见到彼此,所以我们迫切地希望赋予每一个生物姓名并牢记它们。

在《敬亭山记》这首诗中,李少君对自然、时间、人类活动和诗歌之间的关系进行了另一种有趣的思考。这首四节诗的每一节都以“我们所有的努力都抵不上”这句话开头。前两节分别展现了“春风”和“一飞冲天的鸟”。一切都很美好。然而,第三节歌颂的是“敬亭山上的一个亭子”,这是人类的作品而非大自然的杰作。更有趣的是,最后一节以“诗篇”为主角进行特写,而非植物或动物:

我们所有的努力都抵不上

李白斗酒写下的诗篇

它使我们在此相聚畅饮长啸

忘却了古今之异

消泯于山水之间

我们再次注意到,在这部作品中,作者并没有将自然现象和文化现象真正的分离。相反,它们被表现为一个支撑和赋予人类存在价值的连续体。

通常,对大自然的变化或脆弱性的感知会复苏重要的记忆或集结成诗歌。这里非常有必要完整地引用短诗《一块石头》,来鉴赏这采用连续性修辞手法所呈现的效果:

《一块石头》

一块石头从山岩上滚下

引起了一连串的混乱

小草哎呦喊疼,蚱蜢跳开

蜗牛躲避不及,缩起了头

蝴蝶忙不迭地闪,再闪

小溪被连带着溅起了浪花

石头落入一堆石头之中

——才安顿下来

石头嵌入其他石头当中

最终被泥土和杂草掩埋

很多年以后,我回忆起童年时代看到的这一幕

才发现这块石头其实是落入了我的心底

起初,石头的偶然掉落似乎没有特定的意义。但随着石头(和诗)积聚动力,我们看到了波及到世界的影响力。在石头最终落定之前,几只小动物被惊扰了。紧接着,石头经过一系列自然进程被掩埋,并被覆盖上了新的植被。这首诗第一节短小、快节奏的细节描述,被随后第二节缓慢的地貌发展过程所取代。结尾的对句通过象征共鸣,呈现出一个复杂而令人心满意足的结果。岁月流逝,那块石头依然留在诗人心中,也留在了这首诗里。经验丰富且敏感的读者,会注意到这里的掩埋暗示了人类的生死。在诗的开头,那块被埋葬的石头充满了活力,如今,它已经成为一了一首不朽之作。

时间的流逝在本诗集中彰显了出来,无论是个人还是更为普遍的情况,消亡的威胁从未远离。诗集的前半部分,有一首诗叫作《尼洋河畔》。诗人以对一位纽约旅人的回忆开头,这位旅人说,世界各地的生活和爱情都是一样的。诗人并不认同这一说法,并开始称赞林芝是一个非常特别的地方——丛林环绕的泻湖、鲜花、彩虹、霞光和“时有神迹圣意闪烁的雪域高峰”。但这首诗的后半部分,揭示了这个地方对诗人来说如此特别的真正原因。他无意中听到两个年轻恋人害羞地交谈,女孩的声音唤醒了几十年前的强烈记忆:

这声音多像四十年前我听到过的

这黑夜,这激流制造的不平静

也是一样的

因此,诗人是在回忆过去的爱人。他们失去联系了吗?几乎可以肯定,是的。那位女士过世了吗?读者很可能在回味“时有神迹圣意闪烁”,以及太阳的“霞光”这些前段的暗示性词句时,会有这样的感觉。难道这不是在暗示她的尘世生活已经过去一段时间了吗?我们再次感受到对时间的恐惧,以及面对死亡时深切、不安的颤抖。

李少君的一些最令人难忘的诗句与叙事维度有关。例如,在《渡》中,一个站在渡口码头附近的旅行者的短镜头,有一种近乎电影的品质。夜幕降临,诗人、读者,以及这位旅人都不知道自己该何去何从。黄昏时分,雾气透过树林,与他的迷失相呼应。他迷路了。他不记得他为什么在那里,也不记得他应该去哪里。这首有力的小诗再次体现了一种象征共鸣,示意那些觉得自己失去了控制和生活目标的人。

这些包含暗示性故事的诗歌,可以达到一种近乎梦幻的境界。同类作品中最好的例子,或许就是《海之传说》了,这是一首充满魔法的夜曲,描述了转瞬即逝的景象。记忆在发光,但闪烁着忧伤的光芒。正如李的许多作品一样,我们正在见证一个无法长久维持的美好瞬间,但却通过诗歌艺术得以保存:

《海之传说》

伊端坐于中央,星星垂于四野

草虾花蟹和鳗鲡献舞于宫殿

鲸鱼是先行小分队,海鸥踏浪而来

大幕拉开,满天都是星光璀璨

我正坐在海角的礁石上小憩

风帘荡漾,风铃碰响

月光下的海面如琉璃般光滑

我内心的波浪还没有涌动……

然后,她浪花一样粲然而笑

海浪哗然,争相传递

抵达我耳边时已只有一小声呢喃

但就那么一小声,让我从此失魂落魄

成了海天之间的那个为情而流浪者

彼得·休斯2022年于美国贝塞斯达

英文原稿:

Preface to The Selected Poems of Li Shaojun

Li Shaojun is well known as ‘a poet of nature’ for his frequent references to the mountains and plains, leaves and forests, rain and rivers, cloudscapes and oceans, as well as the creatures that inhabit the earth. But his poems always contain a human dimension and betray the emotions and attitudes of the narrator. In fact his most fully achieved work provides insight into the human condition and our insatiable desire to belong to this world and to resist the ravages of time.

It is, of course, true that his poems frequently refer to natural phenomena. In the poem ‘Hello, West Lake’, for example, we are introduced to no fewer than seven species of plants in the very first four-line stanza:

The aroma of the lotus and the breeze soften the courtyard,

home of crape myrtle, magnolia, camphor, ginkgo, and parasol trees

in the sound of bird songs and weeping willows,

a poetic space with a downtempo rhythm, suitable for rhymes.

This is not just a list of names. We are invited to register the the movement of the breeze which carries the scent of those plants as well as the sound of the bird song. And all this, we are told, constitutes a ‘poetic space’ with slow rhythms that are appropriate for poetry. So the literary evocations are as much about art as they are about ‘nature’.

Similarly, in stanza two, the presence of the wildfowl and the squirrel are not presented neutrally. Instead, the meeting of poet and bird startles each of them so that the duck sheers away in fear. And we infer that this disturbance is what makes the squirrel dart away from the observer towards the forest. Then in stanza three the birds foraging in the grass ‘flee as I come’. The fourth and concluding stanza of the poem states:

All of these make me desperately wish

to acquaint myself with every plant and animal here…

The effect of the poem is therefore to makes the reader feel that nature is fragile and precarious. The creatures are always ready to flee from us, perhaps never to be seen again, hence the desperate wish to name and remember every creature.

In the poem ‘Jingting Mountain’ Li Shaojun creates another interesting meditation on the relation between nature, time, human activity and poetry. Each of the four stanzas begins with the line ‘None of our work can compare’. The first two stanzas list respectively ‘the spring breeze’ and ‘the bird that soars’. So far, so good. But the third stanza celebrates ‘the pavilion on Jingting Mountain’, a work of mankind rather than nature. What is even more interesting is that the final stanza features ‘poetry’ rather than a plant or creature:

None of our work can compare

with the verse of the wine-soaked Li Bai.

His poetry summons us here to tipple and wail,

to forget the differences between new and old eras,

to lose ourselves amongst mountains and valleys.

Again we notice that natural and cultural phenomena are not really separated in this work. Rather they are presented as a continuum that underpins and gives value to human existence.

Often the perception of change or fragility in nature will lead to a significant memory, or poem. It is worth quoting the short poem ‘A Stone’ in full to appreciate the accumulating rhetorical effect:

‘A Stone’

A stone rolled down the cliff,

wreaking havoc.

The grass ouched; a grasshopper jumped away;

a snail was too slow to run and shrank its head;

a butterfly fluttered this way and that way;

the creek down at the bottom kicked up a big splash.

The stone fell on a pile of other stones

— and finally settled down.

Lodged between other stones,

it was eventually covered by soil and weeds.

Years later, I recalled this childhood scene,

and realized that the stone had fallen into my heart.

The random movement of the stone might initially seem an event withoutvsignificance. But as the stone (and the poem) gathers momentum we see the effects rippling out into the world. Several small animals are disrupted before the stone finally comes to rest. It is then buried by natural processes and covered with new plant growth. The tiny, quick details of the first stanza of this poem give way to slow geomorphological processes in stanza two. The concluding couplet presents a complex and satisfying conclusion by achieving a symbolic resonance. Years pass and the stone is lodged in the poet’s heart, and in this poem. But if we are experienced and sensitive readers we will note that this burial is suggestive of a human life and death. And the poem has become a kind of immortality for the buried stone that was so full of movement at the start of the poem.

The passing of time is registered throughout this collection and the threat of extinction, whether personal or more generally, is never far away. Early on in the book there is a poem called ‘By Niyang River’. The poet begins by remembering the words of a traveller in New York who said that life and love are the same the world over. The poet disagrees and starts praising Linzhi as a very special place because of its tree-girt lagoon, its flowers, rainbows, sun halos and the ‘miraculous angelic glow of its snow mountain’. But the second half of this poem betrays the the real reason why this location is so special to the narrator. He overhears two young lovers shyly talking and the voice of the girl awakens a powerful memory from decades before:

Her voice, so familiar, brought back a memory from 40 years ago.

This dark night, the splashes from the rushing water

felt familiar, too.

So the poet is recalling a lover from the past. Have they lost touch? Almost certainly. Has the woman died? The reader may well think so on rereading those earlier hints: the ‘miraculous angelic glow’, and the sun ‘halos’. Do they not suggest that her earthly life was over some time ago? Again we sense the fear of time, the deep uneasy quake of mortality. Some of Li Shaojun’s most memorable verses have to do with a narrative dimension. In ‘Ferry Crossing’, for example, there is an almost cinematic quality to this short vignette about a traveller standing near the ferry terminus. Night is falling and neither he nor the poet nor the reader is sure how he ended up there. The moment of dusk as the mist appears through the trees , chimes with the man’s absence of direction. He has lost his way. He cannot remember why he is there, or where he was supposed to be going. Again, this potent little poem attains a symbolic resonance representing anyone who feels they have lost control and purpose in their life.

These poems which hint at stories can achieve an almost visionary presence. Perhaps the best example of this kind is ‘Legend of the Sea’, a magical nocturne suggestive of a fleeting vision. The memory glows, but it glows with a sad light. As in so much of Li Shaojun’s writing we are witnessing a moment of beauty that could not endure, but which has been preserved through the art of poetry:

‘Legend of the Sea’

She sat in the middle of the sea, surrounded by constellations.

Shrimps, crabs, eels performed a dance in her palace.

A brigade of whales ushered in the troupe, followed by seagulls treading water,

then the curtain opened — it was a starry, starry night.

I sat on the reef on a headland.

The wind was fluttering, sending the chimes ringing.

In the moonlight the sea looked translucent,

and the waves in my heart had not yet surged. . .

Then she laughed, delightful and playful like a wave.

The billows carried her laughter to the other side of the sea,

but it had faded into a whisper when it reached my ears.

But this tiny whisper was enough to steal my heart,

and turned me into a seeker at sea for the love that came only so briefly.

Peter Hughes ,Bethesda ,March 2022

诗集作者及专家介绍

诗歌作者

李少君

Li Shaojun

李少君,1967年生,湖南湘乡人,1989年毕业于武汉大学新闻系,主要著作有《自然集》、《草根集》、《海天集》、《应该对春天有所表示》等十六部,被誉为“自然诗人”。曾任《天涯》杂志主编,现为《诗刊》主编。

序言作者

彼得·休斯

Peter Hughes

彼得·休斯(Peter Hughes),诗人、创意写作教师、蛎鹬出版社(Oystercatcher Press)创始编辑。出生于英国牛津市,曾在意大利生活数年,目前主要生活在威尔士北部地区。2013年,他的诗歌选集与《对特殊事物的直觉:彼得·休斯诗歌评论集》(‘An intuition of the particular’: some essays on the poetry of Peter Hughes)同时由Shearsman出版社出版。他根据意大利经典创作了《十分坦率》(Quite Frankly,Reality Street出版社)、《卡瓦尔康蒂》(Cavalcanty,Carcanet出版社)、《via Leopardi 21》(Equipage出版社)等众多充满创意的作品,广受好评。

彼得是剑桥大学朱迪斯·威尔逊基金诗歌项目的客座专家,以及剑桥大学莫德林学院在诗歌领域的客座院士。近期出版的作品包括:2019年的《柏林雾沫》(A Berlin Entrainment,Shearsman出版社)、2020年的《毕士大星座》(Bethesda Constellations,蛎鹬出版社)等。

彼得也是康河出版社的老朋友了,曾在2015年参加了剑桥徐志摩诗歌艺术节。

译者

王美富

Wang Fumei

1958年出生于台湾,现任《廿一世纪中国诗歌》主编兼翻译。台湾大学文系学士,加州大学气象学硕士,普渡大学交通工程硕士。曾任世界银行交通专家,美国交通部工程师。诗歌散见于美国与中国文学刊物。王美富定居于伦敦,全心投入文学。

苏浪禹

Michael Truman Soper

苏浪禹,1946 生,美国华盛顿市人,曾任报社编辑,潜水艇水手,美国政府行政主管。对中国文字和诗歌有浓厚兴趣。他的著作包括四本个人诗集。

主编:游心泉

编辑 & 运营:李玥

(本篇文章内容获诗歌作者李少君和序言作者彼得·休斯授权。)

来源: 瑾萱,康河书店与艺术中心 2023-12-31